Introduction

For new collectors, provenance can feel like a mysterious layer of paperwork. Auction catalogues, gallery invoices, and certificates of authenticity often arrive with an artwork, but what do they really tell you? More importantly, how can you tell if they can be trusted?

Provenance documents are more than administrative records. They are the evidence that establishes an artwork’s journey through time — who owned it, where it was displayed, and how it entered the market. Learning how to read them is a skill that separates cautious buyers from those who risk falling for fakes or inflated values.

In this guide, you’ll learn how to interpret the most common provenance documents, spot inconsistencies, and cross-check information. For a broader context on provenance, see our Ultimate Guide to Art Provenance.

What Counts as a Provenance Document?

Not every piece of paper that accompanies an artwork qualifies as provenance. The key lies in whether it establishes ownership history, authenticity, or exhibition record.

Core Provenance Documents

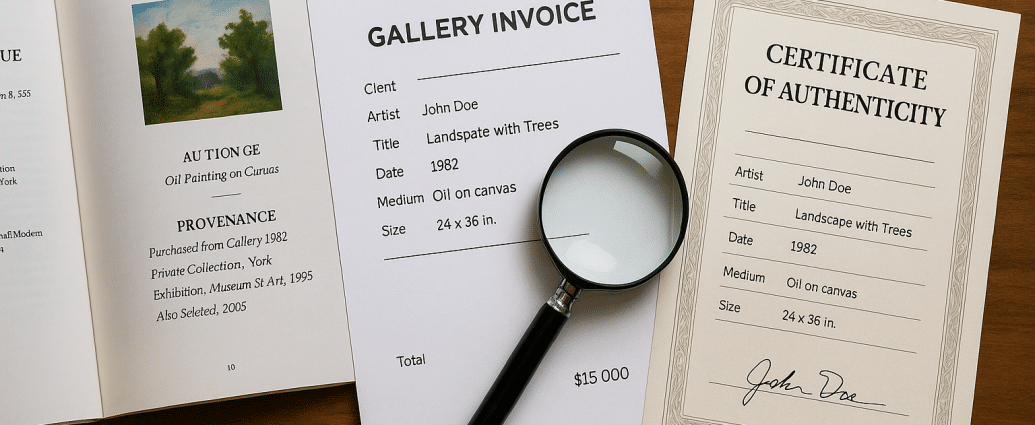

- Gallery invoices or receipts: The original point of sale, listing artist, title, medium, size, and price.

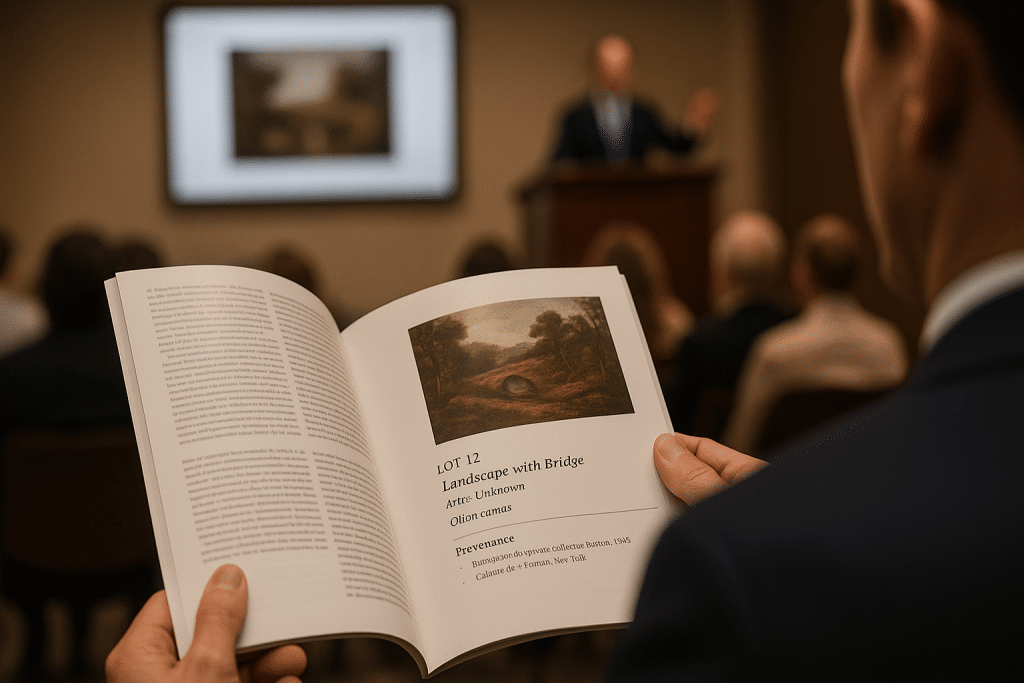

- Auction records: Catalogues or online listings from reputable auction houses (Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Bonhams).

- Certificates of authenticity: Official confirmation issued by the artist, estate, or representing gallery.

- Exhibition catalogues: Proof of public display in a gallery or museum.

- Catalogue raisonnés: Scholarly publications of an artist’s complete works, sometimes including provenance notes.

Supporting Documents

- Condition reports from sales, loans, or restoration.

- Photographs in situ (artwork hanging in a collector’s home or a museum exhibition).

- Expert opinions or appraisals with signatures and dates.

For visual examples, see our keystone article The Ultimate Guide to Art Provenance.

Anatomy of a Provenance Record

Let’s break down the key sections you’re likely to encounter.

1. Artist Details

- Full name, sometimes with birth and death dates.

- Watch out for misspellings or inconsistent use of initials — these may indicate careless or falsified documents.

2. Title and Medium

- Should match the physical artwork exactly.

- Cross-check that the medium (oil, lithograph, sculpture, etc.) aligns with the object itself.

3. Dimensions

- Dimensions should correspond to the work (excluding frame unless noted).

- A mismatch here is a red flag.

4. Date of Creation

- Listed in catalogues or invoices.

- Cross-check with catalogues raisonnés or artist monographs for consistency.

5. Ownership History

- Usually presented as a list, from earliest known to current owner.

- Example:

- Purchased from Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1905

- Private collection, London, acquired 1922

- Sotheby’s London, 1976, Lot 55

- Vague entries such as “Private collection, Europe” should raise questions.

6. Exhibitions and Publications

- Exhibitions: provides evidence of public display.

- Publications: catalogue raisonnés or scholarly references.

How to Spot Inconsistencies

Even professional-looking documents can conceal weaknesses. Pay close attention to:

- Gaps in ownership history — decades without documentation are problematic.

- Mismatch between medium and description — e.g., document says “oil on canvas” but work is acrylic.

- Overly generic terms like “renowned collector” instead of names.

- Altered or low-quality certificates — poor print quality, missing seals, or unsigned forms.

- Conflicting dates between invoices, certificates, and condition reports.

For a dedicated breakdown of warning signs, see Top Provenance Red Flags Every Collector Should Know.

Gallery Invoices vs. Auction Records

Both are valuable, but they serve different purposes.

- Gallery invoice: Establishes primary sale or early ownership. Especially strong if the gallery represented the artist.

- Auction record: Creates a public record of sale at a specific time and place. Useful for tracking secondary-market value.

The strongest provenance will combine both, ideally with continuity between them.

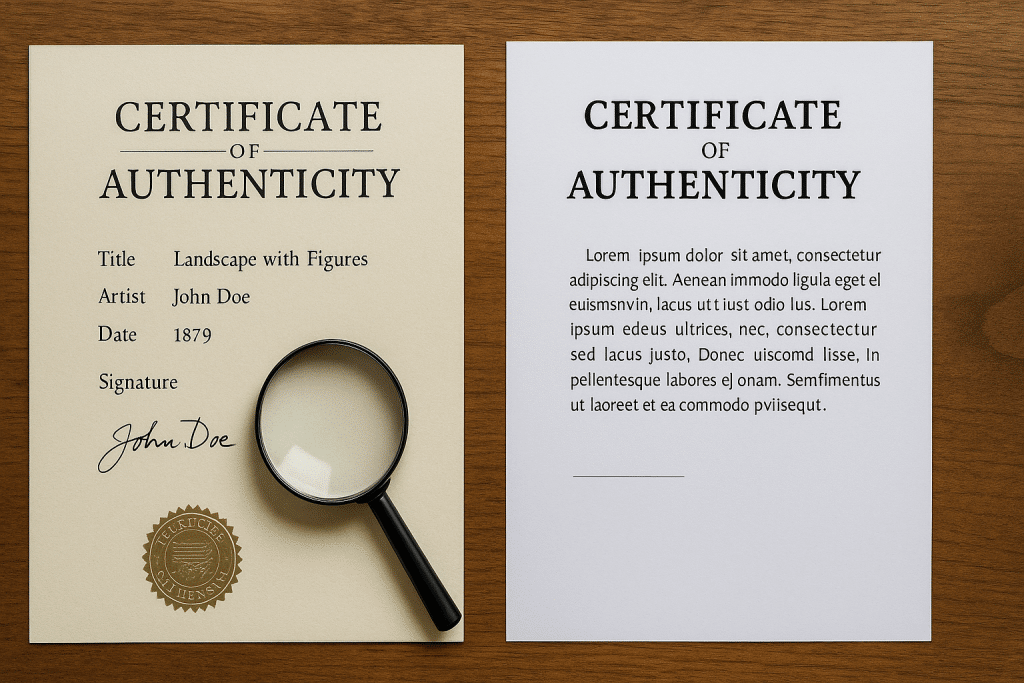

Certificates of Authenticity: What to Look For

Certificates of authenticity (COAs) are among the most commonly misunderstood provenance documents.

- Who issued it? Artist, estate, or recognised gallery are trustworthy sources. A certificate from a dealer with no link to the artist is weaker.

- What details are included? Title, medium, dimensions, creation date, signature, and ideally an image of the work.

- Physical characteristics: Embossed seal, high-quality paper, and handwritten or original signatures add credibility.

A COA alone is not sufficient. It must align with other provenance evidence.

How to Cross-Check Provenance

Even genuine documents need verification. Here’s how to go deeper:

- Catalogue raisonnés: Compare listed works with the one you are considering.

- Auction databases: Platforms like Artnet, Artprice, and MutualArt archive sales results.

- Institutional records: Museums or artist foundations sometimes provide searchable databases.

- Contact galleries or estates: If an invoice lists a gallery, confirm with the gallery or archive.

- Hire a provenance researcher: For high-value purchases, professionals can trace and verify ownership.

Practical Example: Reading a Provenance Entry

Imagine you are reading a catalogue entry for a painting:

Provenance:

- Galerie Maeght, Paris, acquired directly from the artist in 1962

- Private collection, Geneva, 1974

- Sotheby’s, London, 1991, lot 112

- Current private collection, London

This is a strong provenance. It shows:

- Direct link from artist to reputable gallery.

- Named location and year of acquisition.

- Public record at Sotheby’s, verifiable in auction archives.

- Continuity up to the present owner.

If instead the entry read:

- “Private collection, Europe, 1960s–1990s”

- “Acquired from an unknown dealer, 1991”

…it would be considered weak and questionable.

Why Reading Provenance Matters

Understanding provenance is not only about protecting yourself from fraud. It also:

- Enhances the cultural and historical value of your collection.

- Strengthens resale value and liquidity.

- Provides security for insurance and estate planning.

For a deeper dive into value, see Provenance and Art Value: Why History Shapes Price.

Quick Checklist: How to Read Provenance Like a Pro

- Does the document include full artist, title, medium, dimensions, and date?

- Are ownership records continuous, specific, and verifiable?

- Do certificates come from the artist, estate, or reputable gallery?

- Do auction listings align with catalogue raisonnés or scholarly references?

- Are there unexplained gaps or contradictions?

- Have you cross-checked using databases or institutional sources?

Conclusion

Learning to read provenance documents is one of the most practical skills you can develop as a collector. It empowers you to separate reliable records from questionable claims and ensures that every artwork you acquire is backed by trustworthy evidence.

By combining careful reading with cross-checking and expert support when needed, you protect your investment and contribute to the transparency of the art market.

For further guidance, explore:

1 Comment